One way to understand meditation practice is to see it as similar to the habit of physical exercise and working out, which is something that more people are familiar with and able to understand. We can see mindfulness practice as a kind of mental and spiritual exercise; it is a way to strengthen some of our mental “muscles”, for example intentionally directing our awareness to stay where we intend it to stay, or to bringing a spacious, open, accepting quality to our perceptions. In fact, just as physical exercise can improve the health of the physical construction of our bodies, regular meditation literally changes the structure of our brains (for example, a thicker prefrontal cortex).

Below is a list of attributes that many people perhaps already know to be true about the habit of physical exercise (as a method to develop the health of our bodies) but may not yet fully understand as being also true about mindfulness meditation practice (as a method to develop the health of our minds and “souls”):

● Both of them are “good”.

In fact, when done regularly and “correctly”, many of the positive results of physical exercise and meditation practice are similar. Both of them generally:

— boost positive moods like ease, joy, relaxation, peace, and well-being

— increase levels of energy and vigor

— create an open, bubbling, pleasantly vital flow of energy in the body

— help sharpen thinking and deepen concentration

— help a person to live a life that is less addictive, more intentional, more free, and full of positive will power (in part by getting over our resistance to the discomfort of doing them)

— improve the restfulness of our sleep

— increase confidence and self-esteem

— reduce depression, anxiety, and distress, more optimism and positivity

— create capacity to hold space for physical pain and emotional challenge without being crushed but it

— feeling more present and “in the now”, helping to take a break from the tangled swirl of thinking, worries, and obligations that many of us often find ourselves caught in

— provide a time to reflect, to get perspective, and to be aware of life issues with less reactivity than normal, and, in doing so, to let deeper wisdom and guidance bubble up

In fact, many people have said to me over the years that “exercise is my meditation”. Before I started meditating, I also felt this way, perhaps because it was when I went running that I experienced relaxation, release of tension, centering, freedom from compulsive thought, a spacious time for insight to arise, and many of the other benefits that I now also get from meditation practice.

Regarding others, I have come to perceive that the factors that have motivated me both to meditate and to exercise are combined for many people into just a one single motivation, just towards exercise.

● For both working out and meditation, in order to experience those positive results, we need to put time, energy, and effort into actually doing them. We need to keep at them and take action on a regular basis, making them part of our life schedule with some degree of frequency.

In order to build a base of skills and train up our abilities – whether those skills are an ability to lift heavier objects, run father and faster, have fewer heart attacks, concentrate better, or surf emotional energies with ease – need to take action for a while. The frequency of our practice slowly builds our base of strength.

● There are times when both exercising and meditating produce dramatic, immediate, and easily perceivable positive changes. Rapid improvement like this happens especially often for beginners.

Mostly, though, the positive changes that come from exercise and meditation are gradual, small, slow, incremental, subtle, and almost imperceptible. It can be weeks or months before we notice the results of our efforts. Noteworthy progress is usually only visible after we look back over significant periods of time.

It’s relatively easy to start a new exercise plan or meditation practice with great enthusiasm, but sometimes it can be harder to keep it going. Early enthusiasm can droop and the novelty of something new can lose its shine. When that happens, it’s worth remembering that positive change takes time, effort, and perseverance.

We can sometimes plateau with our improvements, and feel stuck, bored, or like not much is happening or changing. But then we then might take on a fresh approach or technique that breaks us out and shifts us into a new cycle of growth. These are normal phases of our path of training.

In general, with both exercising and meditating, some days might feel strong and pleasant, and some days might feel weak and unpleasant. We might experience positive progress on a given day, but we also might not. But, like the stock market, the long-term curve trends upward, even if there are more local ups and downs.

● Both working out and meditating can feel uncomfortable, repetitive, tiring, frustrating, effortful, boring, painful, and challenging. At those times, the best thing for us to do is to push through and get our session in. Even when their practice is challenging and painful, an athlete or meditator is often making progress and building long-term strength, skill, and health.

With both, it is common to not want to start, but to feel great afterwards and be glad one accomplished one’s practice. Regardless of whether we enjoy this afterglow or not, the main sign as to whether we had a healthy workout or meditation is not whether it felt pleasant or unpleasant. We can know that it was successful simply by the fact that we actually did it.

(as an aside – for years, when I have told people that I am going on an extended meditation retreat, many people who have never been on a sitting retreat have responded by saying something like, “Oh, lucky you! That sounds so peaceful, like such bliss”. It has always seemed like a funny way for them to respond. Going to a meditation retreat not a relaxing vacation. I mean, yeah, I usually look forward to sitting retreats, I do feel fortunate to have the time to go and do them, and I usually do feel some episodes of “bliss” while on them. But it’s also hard work – like going to an exercise camp with hours a day of working out.)

● And, yes, both working out and meditating can sometimes feel like “bliss” – in the zone and in the flow, flying along effortlessly.

When we can feel enjoyment and pleasure in our sessions, it helps to intentionally ride and enjoy those good feelings as a way of motivating us to do more of them in the future. And when our practice feels unpleasant, it can sometimes help us to find a pleasure in it, to find a healthy sweet spot, also as a way of motivating us to continue.

● There is no one type of physical exercise or meditation that is appropriate for all people at all times. The best choice at any point depends on the specifics of a person’s current state and on their future goals.

There are different types of working out that have different purposes, for example. Some exercises seek to develop muscular strength, some joint and ligament flexibility, some agility, some cardiovascular conditioning and endurance, some weight loss, and some muscle toning.

Similarly, there are different types of meditation practices that seek to cultivate different mental faculties. Some practices seek to develop concentration power, some warm-hearted lovingness and interconnectedness, some grounding in the body, some freedom from the tangle of thinking, and some a general experience of spiritual, spacious openness.

And just as pieces of exercise equipment might have different settings – different heaviness of weights or different angles of motion, so meditation often has different settings – how long to sit for, eyes open or closed, spoken labels or quiet, practicing in motion or sitting, etc.

● When developing a new exercise or meditation practice, it works best to start small, with bite-sized, do-able goals and expectations.

Just as, for most people, it would be counterproductive to start a new work out plan by promising to bench press a massive rack of lead, to take five pilates classes back-to-back, or to run twenty miles every day, it is usually not a good idea to start a meditation practice by intending to sit for an hour every morning and then another hour each night. In both cases, setting an overly ambitious intention like that is likely to quickly leave a person feeling demoralized and overwhelmed, and quitting.

It usually works better instead to start out with an intention like to get on an elliptical or to sit in silence for ten minutes per session, two sessions a week. Once that within-reach commitment starts to feels comfortable, the new practitioner can then push themselves, little by little, to go further.

The Dalai Lama is quoted as having said, “Moderate effort over a long period of time is important, no matter what you are trying to do. One brings failure on oneself by working extremely hard at the beginning, attempting to do too much and then giving it all up after a short time. A constant stream of moderate effort is needed.”

● The techniques of working out and meditating can seem pretty silly on the surface – if we step back and think about it, it’s actually kinda weird to lift dull chunks of metal up and down, or to run on a treadmill without getting anywhere, or to count how many times we breathe. In each case, however, as we know, the point is not just doing the action itself, but it is more the way in which doing those actions train, change, and mold us.

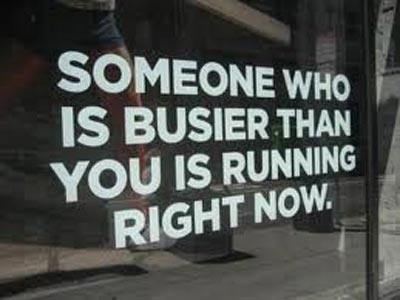

● If we have worked out or meditated at any point in our lives and have experienced firsthand how healthy it is for us, but we are not currently doing much of it, then we are almost always avoiding it not because we are too busy (which is what we often tell ourselves) but actually because we don’t want to feel uncomfortable.

● Where a person first starts working out or meditating regularly, and they are “out of shape”, there is an initial discomfort, unpleasantness, and pain to get through – experiences like soreness and fatigue for exercise, and restlessness, boredom, and confronting emotions for meditators. These difficulties are part of starting on a process of training and adaptation.

Once a person has gotten in a consistent habit of practicing regularly, though, it can feel relatively easy to jump into starting a normal session. The practitioner has built reliance, stamina, health, and clarity, which results in ease.

But both are practices, not a one-time fix. If an athlete is in intensive training and works out hard but then backs down into lethargic inactivity, they will probably stay in good shape for while, their body will eventually start to sag, have heart problems, lose tone, put on fat, lose flexibility, etc. They will probably be in better shape than if they had never worked out, but we can’t just exercise hard for a while, and then, that’s it, we’re in great shape for the rest of our lives. As we all know, to stay healthy, we usually need to stick with an ongoing exercise practice.

I have noticed that there is something similar that happens after doing intensive residential meditation retreats. There is a momentum of positive impact that lasts for a while afterwards. To stay mindful, clear, and free, however, we generally need to keep up with a regular meditation practice.

If the person for any reason takes a break and stops practicing for a while, though, it can be difficult to start back up again. There can feel like a renewed barrier of achey, gross discomfort to break through when trying to get back into it.

● There are activities that we can indulge in that deeply and quickly reverse and dissipate the good effects that we get from working out or meditating. In fact, they are often the same– television, cigarettes, donuts, trying to do too much while sleeping too little, stuffing down emotions, porn, cocaine – you probably already know the list.

● Both meditation and physical exercise work best if we relax and breathe deeply, and are not tightening up and trying to grit our teeth and grind our way through.

● Both exercise and meditation are more effective and stable when we have some intentional transitions to ease in and out of a session. We have less of a chance of injury if we have warm-ups like stretching and cool-downs like slowly decreasing our pace and intensity at the end of out workout. Similarly, meditation works best if we have some “ceremonial” aspects at the beginning and end, like deep breaths, bows, intention-setting, and gratitude.

● For both, it can be helpful set an intention or goal for how often, for what duration, and in what way we intend to practice, and keep our word with ourselves and follow through. Sometimes getting our session in is a question of choosing discipline, and “doing it anyway”, over motivation and “feeling like it”. And sometimes having a long-term goal – for example, to complete a marathon or overcome anxiety issues – can help us to more feel like it in the short term.

● When lifting weights, the final rep out of fifteen can be the one where most of the benefit of strength increase actually happens. It is in those final few seconds that the muscles micro-rip the most, setting up the strengthening repair that will follow. In a way, the main long-term value of the previous fourteen reps was only to stress the muscle to the point where the painful gain of that final fifteenth rep was made possible.

Something similar can happen in a meditation sit when the first thirty five minutes feel like smooth sailing, but then in the final five minutes arises an almost intolerable “time to get on with the real world” antsiness. It may turn out that dissipating that last-minute agitation through opening to and fully and consciously experiencing it will be the main long-term value of that meditation sitting. In this view, the usefuless of the previous thirty-five minutes of meditation was simply to create enough stress that that discomfort with simply being human – which has been lurking somewhere in the subconscious, poisoning one’s experience of life – is brought up to the surface so that it could be mindfully evaporated.

● If an athlete wants to be ready and perform when the pressure is on, the time to train by practicing in the same skill again and again during the off-season or between games. Similarly, if we are able to call on the capacity to be focused, open, and aware when life is especially confusing, painful, and overwhelming, we can train by meditating when life is relatively simple and calm.

● With both meditation and sports, it can be interesting and inspiring to learn about some of the more sensational accomplishments that humans have made. We may hear that Olympic powerlifters can bench press 1,000 pounds, or that a man once swam fifty hours straight across the Adriatic Sea without taking a break, and that can ideally inspire us to let go our own beliefs about our physical limits and set our sporting goals even higher.

We know enough however to not try to replicate those feats ourselves right now, though – just because a human body is capable of doing such amazing things does not mean that an untrained person can do so, or could even try without endangering themselves. We understand that such impressive feats are the result of years of all-consuming single-minded commitment and training, not something we should compare ourselves against and feel upset or ashamed about not being able to do, and probably not an even useful goal for most of to aim for, in light of our other life priorities.

These are some good attitudes to take when hearing that some people can rest their awareness inside the sensations of their breath for many hours at a time without a single moment of distraction, or about monks who stay alert and energized while spending months on end meditating eighteen hours a day and sleeping just two hours a night. Yes, after extreme commitment and training, a human is actually possible of doing such things, and we can be inspired and uplifted by their amazing accomplishments. But, no, we should not feel at all badly that we, at our current level of training, are unable to, and we shouldn’t try to replicate their impressive feats.

Many people are more understanding with themselves that they couldn’t run ten miles or bicycle fifty without stopping. When unable to drive all day for three days and stay focused, or handle all the challenges of daily life without becoming overwhelmed, they just assume that they should be able to. It often doesn’t occur to them that there is a training that they haven’t done but could.

● For years, I have kept a log of how many minutes each day I have spent exercising and how many meditating. Doing that has inspired me to do so more often and to put more time into both of them.

● With both practices, we are aiming for a positive transformation that is present in our whole life, a permanent elevation in health that aids us in all our activities and situations. When we work out, we’re not trying to get into states of strength, vitality, flexibility, and conditioning that are only present while we the exercises and then vanish during the rest of the day; we’re instead trying to gradually increase our baseline level of ongoing physical health. In the same way, our goal in our formal meditation practice, sitting say for half an hour each morning, is not to achieve a temporary state of clarity, calm, and equanimity that is only present during our session and then vanishes during the rest of the day – we are developing those traits so that they are with us at all times.

● Being active in daily life – walking or riding a bicycle on short journeys instead of driving, helping a friend to move some furniture, taking the stairs instead of the elevator – can make it easier to develop physical health through formal workouts. Doing formal workouts, conversely, usually makes it easier to be active during the rest of our day.

Similarly, being mindful in daily life – being aware of body sensations and thoughts while walking from one place to another, or paying attention to the present moment while doing house cleaning – is mutually supportive with formally meditating while sitting still on a cushion first thing upon waking up.

● There are times when an injured joint in a person’s body is not ever going to fully heal or get back to ideal health in this lifetime – it is just going to be sore for the rest of their life whenever they work out, no matter how much stretching, supplements, rehabilitation, treatment, or surgery the person tries. In such situations, there is not much that they can do except accept the pain of the injury, and have a bad ass work out (and life) anyway.

Similarly, some of the difficult and painful psychological phenomena that we sometimes encounter in meditation – for example, certain types of traumatic memories, shame and self-esteem challenges, and manipulative habits of mind – are not going to fully get to an ideal state in this lifetime, no matter how much we pursue paths of change like meditation, psychotherapy, workshops, artistic expression, and deep personal connection. The best thing that we can do is accept these difficult aspects of ourselves the way that they are, and have a deep and solid meditation (and life) anyway.

● With both working out and meditation practice, social support and accountability can help us to make more rapid progress than we otherwise would make. Attending an exercise class or sitting with a meditation group may have us push ourselves beyond what would otherwise be comfortable and where we might stop on our own. It can inspire us to dig in and work longer, with greater vigor, and with greater focus and intentionality. Similarly, having a buddy show up at our door at an appointed time to go with us on a walk, bike ride, or run, or a friend exchange texts with us as we both sit down miles apart to do our daily sitting, make it more likely that we get our daily health practice in.

● To develop an effective beginner practice with either exercise or meditation, we usually need to take some time to learn new procedures that we are not already familiar with and to develop new skills.

● If we are serious about exercising or meditating, we may need to work with a competent and experienced trainer, instructor, teacher, coach, or guide so as to have our practice be most effective. They can ask us questions to get a sense of our experiences and goals, and then give informed and useful practice assignments. They can give us instruction so as to have our efforts be most effective and not dangerous.

Some of my exercise coaches have helped me improve my technique by teaching me what I didn’t know that I didn’t know – for example, that my elbow was flying out as I threw a jab punch and that I would gain more power by keeping my elbow in on the main line of movement. I have performed a similar role as a meditation teacher for students who told me that their practice felt difficult, unpleasant, and fruitless, where I stepped in and shared ways that they could meditate differently that, when they tried them, helped them to see immediate improvement in experience and results.

With both working out and meditation, we can often get the best results if we take time afterwards for recovery and integration. Rest is essential for muscles to rebuild after lifting, and the benefits of meditation seal in best when we give ourselves time and space afterward to let everything settle.

● Although they are generally beneficial, both exercising or meditating can also be dangerous. The level of risk of overtraining or pushing too hard varies, however, by how “in shape” the athlete or meditator is, the quality of their past training, and the intensity of the physical/mental work out that they are jumping into.

As we all know, people sometimes sprain joints, tear tendons, and have asthmatic episodes, heat strokes, and heart attacks while working out. But, obviously, the risk of damage from working out is probably higher for

— an stiff, overweight, and asthmatic seventy year old with blocked arteries who is who is lifting heavy furniture bending from the waist, or is trying to exercise for the first time in decades by bicycling a hilly fifty miles in the hot sun

compared with

— a twenty year old flexible, strong athlete who works out daily and has gotten guidance from coaches and physical trainers, and who is going out to shoot some hoops with their friends, or walk a mile to the store in moderate weather

Although it is rare, meditation can also occasionally trigger in people panic, memory flooding, depression, anxiety, and, in some of the most extreme cases, manic episodes, psychotic breaks, and suicidal urges. There is however more risk in meditating for a

— socially isolated, hyperanxious person with a background of intense trauma and bipolar episodes who has never meditated before and who jumps straight into an sixteen-hour a day, multi-day retreat with inexperienced teachers who are part of a wacky cult

compared with

— a well-adjusted, emotionally healthy long-time meditator who in the past has learned from wise teachers and who is sitting down to deeply feel their body sensations for fifteen minutes before going to bed

On this topic, one article states, that “Contemplative traditions have long recognized that intensive mindfulness practice can lead to challenging emotional or bodily experiences that require expert guidance. And just as research has shown that working with a well-trained fitness professional reduces the risks of exercise, especially for people with medical conditions, recent studies have also shown that even highly vulnerable participants can practice mindfulness safely if their needs are carefully addressed.”

● While working out, most athletes can usually tell the difference between temporary discomfort – hitting the wall, or being sore the next day – from pain that signals an injury that may be more serious and long-term, like a torn knee tendon.

Similarly, experienced meditators usually come to perceive the difference between temporary mental discomfort, like the strong emotions that sometimes arise after opening up and relaxing the mind, or a temporary physical pain like a leg falling asleep from sitting cross legged, in contrast with more serious and long-term mental or physical troubles that might deteriorate the more one practices, like a deepening depression, or a worsening pain that comes from a nerve that gets pinched when sitting cross legged on a hard cushion.

● It may feel motivating or inspiring to read a book or watch a YouTube about exercising, to copy a great athlete’s mannerisms, to tell people “I’m an athlete”, or to wear workout clothes, but none of those activities will, by themselves, get a person in better shape. Similarly, the spiritual benefits of meditation don’t come about by reading spiritual books, copying the mannerisms of spiritual people, identifying oneself as “spiritual”, or from wearing holy robes – the growth comes about by actually doing meditation practice.

● One final similarly: I feel that both meditation and exercising are often important parts of being a “spiritual” person.

About 1600 years ago, the great Indian teacher Patanjali first formulated what has become the standard path of spiritual practice in the Hindu/yogic tradition. As one would expect, he included meditation, study, devotion, honesty, kindness, and cultivation of awareness of the Divine. He also included “asana” – the system of physical poses and exercises that we in modern world call “yoga”.

900 years earlier, the Buddha formulated his recommended path of spiritual practice in the “Noble Eightfold Path”, a list that is similar to Pananjali’s – meditation, concentration, honesty, respect, ethics, and energetic action – but that does not include asana. I once heard one of my teachers point out, however, that in the ancient Buddhist stories, the Buddha was constantly walking from city to city; lots of physical movement was taken for granted back then. So, my teacher continued, if the Buddha were around today, he would probably teach a “Noble Ninefold Path”, and that he would add “Noble Exercise” to the list of spiritual practices that can take us from constriction and suffering towards a greater experience of depth and liberation.

[

[