Listen to part one of the interview

Listen to part two of the interview

Mark Lewis: Welcome to “Money, Mission and Meaning: Passion at Work, Purpose at Play“, where we explore how we can integrate our personal values and our professional skills to create pleasure and profit in the business of life. I am your host, Mark Michael Lewis of rationalsprituality.com, author of “Relations Dancing: Consciously Getting What You Really Want In Your Dating” and “The Key Is In The Darkness: Opening The Door To A Spiritual Life.”

Today’s guest is Adam Coutts, a meditation teacher and practitioner who has worked with hundreds of individuals and groups to guide them to discover the experience of meditative awareness and to customize a spiritual practice that fits their personality and into their lives. So, join us as we enjoy the power and simplicity of meditation and the profound peace and bliss that comes from learning to rest in awareness and consciousness itself.

Welcome, Adam, it is a pleasure to have you on “Money Mission and Meaning.”

Adam Coutts: It is great to be here, Mark. I have experienced the show on the podcast and on “Personal Life Media”, and I thought “Ah, it would be great to be on the show”. I am excited to be here.

Mark Lewis: Excellent. So, you are a meditation teacher, and I know a lot of people, when they hear about meditation, think that it is some kind of magical, mystical, “New Age” thing, with candles and incense, that involves a guru that you give all your money to, and where you wear orange robes around. Maybe you can help us break it down: what is meditation, as you understand it? And, why would normal Americans benefit by learning about it, and starting a meditation practice?

Adam Coutts: Well, you do actually need candles and incense and a guru and an orange robe! But, yeah, that is besides the point. [Laughing] To be serious, the way that I teach meditation, I teach it in pretty much a traditional Buddhist way. Which is to say, there are basically, as the ancient scriptures put it, two wings to the bird, there are two wheels to the chariot, there are two main aspects to the meditative path. One is what a Westerner who does not meditate might say, “Oh, meditation, that is chilling out. That is emptying your mind.” That is what is traditionally called Samatha, or focus practice. You focus the mind on the breath, for example. Another common Samatha practice focusing the mind focus completely on a mantra, on the soles of the feet while walking, or focusing awareness on the base of a candle flame. Those are some of the common Samatha practices.

Mark Lewis: Samatha is about focusing the mind on a particular part of your experience?

Adam Coutts: That is correct. You divide all of human experience, all the various thoughts and sensations that a human being can have, into two mutually exclusive categories: there is what you are choosing to focus on, and then there is everything else. So, while watching the breath, if you felt a little pain in your knee (unless it was like a severe or a medical emergency, then that is something of course that you would want to take care of), but if you felt your foot fall asleep, or you had a thought about what is for lunch … the idea with Samatha practice, is that you just let those distractions slide away. There is a saying in Japanese Zen, “Body and mind of themselves drop away”. Everything else drops away from the pure experience of breathing in and out, in this example. The benefit of Samatha practice is that a person’s mind is tranquilized, it is focused. Sometimes people try to read something, and they are so emotional that they are like, “I just can not read it. I am just so agitated.” So what Samatha does is it calms choppy waves. It enables the mind to be able to be, as the Tibetan would say, “pliable”. It enables you to rest your mind intentionally and completely on something, and have tranquility, peace, and openness.

The other wing of the bird in Buddhist meditation is called Vipassana, which literally translates into “breaking things down into parts, and seeing them clearly”. So Vipassana is, if you had a pain in the knee, you would be aware of the exact way that that pain in the knee feels, all the little vibrations of it. I have found that a pain in the knee usually consists of some heavy, dull low wave-length vibrations, and also some high frequency vibrations. If you pay attention to such a pain, you notice it consists of all these various waves of energy. So do thoughts, so do sounds that we hear, so do images that we see – they are all vibrating waves of energy, appearing and arising from nothing and then eventually disappearing again. So, the Vipassana practice is having our awareness, having our consciousness, fully accord with the exact shape of the waves that make up all the thoughts and sensations that a human being can encounter.

And the benefit there is that there is a feeling of liberation. There is a feeling … the ultimate point of it, as I see it, if you want to get to that, is seeing through the human game, and seeing the Divinity that is our ultimate Source shining through our experience. That is an advanced stage in the practice, though. Usually there is a lot of difficulty and agitation for people to work through first, but slowly there is more of a sense of attuning with the nature of things, seeing through to the very heart of reality.

It is kind of hard to talk about these things because it is more of an ultimately mystical thing. I guess, more immediately, practically speaking, Vipassana leads to relief from suffering, a sense of knowing one’s self, and a sense of opening the heart, and yeah there are other practical intermediate benefits to Vipassana practice.

So there is a long answer. [Laughing]

Mark Lewis: Exactly. Well, that is the nature of the game. I actually appreciate you taking the time to get into both wings of the bird, or, I like that, wheels of the chariot. It reminds me of the idea that you need both legs to run, and if you specialize in one rather than the other, you are going to end up going in circles. So it sounds like the two different types are: one is where you focus on one thing, and exclude everything else, or you focus on one thing and allow everything else to just kind of come and go …

Adam Coutts: Yep

Mark Lewis: And then the Vipassana is more about allowing everything to be, and to go into what it is. How is the Vipassana different than the Samatha?

Adam Coutts: How is it different? Well, I will give an example of watching the breath. And this is sort of an “advanced level discussion” of this topic, but I will lay it out there anyway. Which is to say … if you were watching the breath as a meditation, the way to use that meditation as a Samatha meditation would be to just be aware of how many times you are breathing, and if you are breathing at all. You would not have to pay so close attention to the actual sensation of breathing. The whole point is just to use the breathing as an anchor to notice when your mind is distracted, and to release those distractions, so as to focus and compose the mind.

So, your mind might get caught in thinking about lunch, thinking about your career, thinking about a fight you just had, you know, you feel a little tingle in your ankle and you think “hey, should I pay attention to that?”, “should I have better posture?” – there are all sorts of things that will pull the mind away. And the idea with Samatha is that breath is an anchor that helps you let go of distractions – gently, without pushing, without pulling, it is not skeet shooting, you are not hostile towards the distractions (that is how a lot of people let go of distractions in meditation, it is a common thing for beginners, but, no, being gentle with oneself), you just notice that the mind is being pulled away. Kind of like if you have a child who you love that was taking candy off the shelf in the store. You just say, “Hey, put the candy back”, and gently, calmly shepherd the kid along. So it is, we come back to the breath. As I said, you would not actually have to pay that much attention to the actual texture of the breath.

Where as, watching the breath can also be more of a Vipassana meditation, and the way that works is you actually feel the subtle feelings of hot and cold coming out through the nose, the cold dry air coming in, and the warm moist air going out. You feel the little feelings of expansion and contraction, pleasure and unpleasantness, the tingles, the vibrations, in the pit of the belly. You actually encounter the richness of how it is to respire in the human body, and you actually feel exactly how that feels.

There is a poem by the singer and poet Leonard Cohen, who was a Zen Buddhist priest for twenty years, actually, he lived in a monastery after his singing career in the sixties. He talked about how an angel of love, or a saint of love, has a mind that accords with true nature of things the way a runway ski caresses the landscape of a hill.

Mark Lewis: Wow!

Adam Coutts: I love that image! It is sort of like the way in Vipassana practice that the awareness just sort of rises and falls with the topography of any experience – the thinking, the sensations in the body – the way a runaway ski might caress a hill.

Mark Lewis: Okay, great, this is exactly were I thought we would get. And we have got right there, because this is … weird.

Adam Coutts: It is weird, I agree with you.

Mark Lewis: As a person born in California and living in San Francisco, and there is lots of weirdness here, the level of thinking that you are talking about, it’s kind of like, it’s the ground that we walk on; it is the space that we live in. So, we do not ever think about this. I remember when I first heard about meditation, like you said, I thought it was some kind of magical, spacey thing.

Adam Coutts: Yeah, yeah

Mark Lewis: But it sounds like it is about learning to direct and focus your mind in precise, consistent, and systematic ways. And, in the process of learning to focus it like that, or learning to actually having it concentrate on one thing for a period of time, that it’s like whole new worlds open up for you. Is that … ?

Adam Coutts: Certainly. And, I want to address that topic, but there is one more thing I want to say about Samatha and Vipassana before we move on; which is, many people are familiar with the yin-yang symbol. What that symbol represents is the way different life energies work together to create a unified whole. And one way of thinking of yin and yang is masculine and feminine energies, I think that that one way that it is translated into American thought patterns. You can say that Samatha represents the masculine side of meditation: it is focused, it is powerful, there is a sense of doing something, it is penetrating, it is disciplined, it is grounded, it has boundaries, it says “no” to distractions, it says “no” to fun, it creates a container, it is pure stillness.

Where as, Vipassana, one could call more the feminine side: it is receptive, it is pure acceptance, it is being, it is expansive, it is welcoming, it has open boundaries, it is intimate, it embraces all, it is in tune with the flow and the motion of life, it is delightful, it is more pleasant. So, just as masculine and feminine work together to create a unified spiritual whole in the ying-yang, so do Samatha and Vipassana, the masculine and the feminine of meditation, work together. I have not heard any of my teachers give that analysis – that is just kind of something that I have come up with on my own – but that is the way that it seems to me.

Mark Lewis: I think that is great. Again, I have this vision of the bird with two wings, or the chariot with two wheels: the masculine and the feminine balance of both kind of focusing and directing your attention to one particular thing and saying no to other things, versus opening your attention so that you can allow it all in and feel in its depths.

Adam Coutts: Yep, I think that, at their best, the two synchronize well together.

Mark Lewis: Fantastic, so we are about to take a break to support our sponsors. When we come back I want to get into how actually learning to focus your mind like this, and to open your mind like this, and how to feel deeper into the texture of the human experience within ourselves so as to actually make a practical difference and a real shift in how you experience the rest of your life. I am Mark Michael Lewis, I am speaking with Adam Coutts, meditation trainer, I will say, extraordinaire …

Adam Coutts: [Laughing] Thank you.

Mark Lewis: Here on “Money, Mission and Meaning: Passion at Work, Purpose at Play. We will be right back.

[Music playing]

Mark Lewis: And we’re back with the meditation teacher Adam Coutts. So, Adam, I know that we both live in the San Francisco Bay Area …

Adam Coutts: Yeah

Mark Lewis: There are a lot of New Age-thinking communities out here, and you hear about crystals, astrology, spirit guides, and manifestation, and sometimes people lump meditation in with that world. I am curious how does all of that kind of stuff, kind of more magical, “spiritual” stuff, how does that fit in with your understanding of meditation, how you actually live meditation, how meditation actually impacts your daily life?

Adam Coutts: Yeah, that is a great question. Well, I think part of the problem there is that when Buddhism was first translated into the west in the nineteenth century they used a lot of Western words, for example the word “enlightenment”. I think that Asian words like “moksha” or “satori” (those two are Sanskrit and Japanese words, respectively) are better translated as “liberation”, than as “enlightenment”. But “enlightenment” was a Western word, you know, Voltaire and the gang, and that is the word that the first translators chose, and that is the word that has stuck.

Similarly the Western word “meditation” already meant a whole lot of things when it started being used to describe Buddhist practice. In the medieval Christian context, if I understand correctly, the word “meditation” meant to contemplate something, to hold an idea of Jesus in mind, or the way a modern American would use the word maybe, to ponder a problem. Whereas I would say the way “Samatha bhavana” and “Vipassana bhavana”, which mean Samatha practice and Vipassana practice, really translate, it’s not that sort of thing, it’s not intentional cultivation of something, with a goal of creating a certain specific mindstate or solving a particular problem. It’s more like, being with what is, letting reality come to you and present itself.

In traditional Buddhist practice, there are practices of cultivation of things like loving-kindness, there are practices where you intentionally generate a sense of loving-kindness within yourself. And I know the Tibetans have – I am less familiar with Tibetan Buddhism than I am with the other Buddhist lineages – but I do know that they have a lot of practices that could be seen as pretty magical. They have a lot of … their lineage evolved later than the other schools of Buddhism, and so, as the Indian Vedic religious context evolved over time and became more colorful and magical, that lineage of Buddhism, what is now Tibetan Buddhism, Vajriana Buddhism, also co-evolved. So, it has a few more rituals of cultivation; the sand mandalas, elaborate rituals involving hypothetical deities, celestial bodhisattvas … so, bottom line, there are aspects of Buddhist consciousness practice, Buddhist “meditation”, that could be seen as involving thought and involving intentional cultivation of specific mindstates.

However, the two schools of thought that I have studied with most – which are Theravada Vipassana Buddhism from Thailand, Burma, and Sri Lanka, and Soto Buddhism from China and Japan – what their meditation traditions more involve is what we have talked about: just being what is, just paying attention to the raw reality of life. It is not something sort of magical and mystical. It is a way of paying attention to breath, paying attention to body sensations, and watching and being aware of the mind have its thoughts.

And the funny thing is, there is a lot in Buddhism where you do simple practices like that, and you eventually pop over to the other side, and does get to be kind of magical and mystical. For example, many people avoid pain by playing their Play Station, by drinking some coffee, getting drunk, watching TV, getting into an argument – whatever we do to avoid pain. Well, there is a way in Buddhist meditative practice of feeling through pain by feeling of a knee pain or emotional pain so fully that the pain ceases to be suffering, because it is experienced so fully. I would say the same thing happens when, by being with the boring reality of being a human being, just feeling how the body feels, just feeling the breath, just being aware of thoughts are thoughts (rather than getting caught in them), there is a way in which you pop through to the other side, and there is something sparkly and almost Divine about it. I have had those experiences while living in monasteries.

And, it is not like a person is intentionally using crystals, or going to a guru and talking about The Absolute, or anything like that. It is just a simple awareness, a matter-of-fact awareness, of what is, and there is something alive that happens. And … yeah, like that.

There is some Zen poetry that talks about that, about how, before enlightenment, the mountains are mountains, and the rivers are rivers. Then a magical thing happens and then it is just, mountains are mountains and rivers are rivers … but something is different. It is hard to say what.

Mark Lewis: As you are saying this, in my book “Key is in the Darkness“, I went through, for my perspective, the lived spirituality and how it actually plays out. One of the central ideas in the book is the idea of Divinity, and the idea of how you relate to the Divinity. One of the things I am hearing in what you are saying is that you can learn both wings of this bird, you can learn to both focus your attention, and actually place it on one aspect of your experience for an extended period of time, and then at the same time you learn to open your attention so that you can feel into the depth of it, so that you can feel its textures, and feel all of its meaning, that … it is sort of like, Henry Miller once said that, when you look at a blade of grass, when you look at anything deeply, you discover a world of mystery and majesty that is so beautiful because the world itself, each part of it, even a blade of grass, is so rich in experience that it is almost overwhelming.

Adam Coutts: Yeah

Mark Lewis: And, what I am hearing you say is that before enlightenment, mountains are mountains, and then after enlightenment, mountains are mountains, except they are different. It is like you are actually experiencing the mountain as a miracle, as something that it is so rich that it impacts you, that is inspires you, that it give you the sense of meaning and participation and bliss. Is that kind of what you are talking about?

Adam Coutts: Absolutely, absolutely. There is a story about a spiritual teacher Ram Dass, who did a two-month retreat in Burma, a meditation retreat where he was in just a little cubicle. Or, a little … what would you call it’s …

Mark Lewis: Hut?

Adam Coutts: It was a room in a building, I guess. They would slide food into him under the door each day, but, other than that, he did not leave this one room. He says that he got the … well, I think Ram Dass is a pretty extroverted person, which is to say he gets bored.

Mark Lewis: [Laughing]

Adam Coutts: Psychology research shows that the more extroverted you are, the more sensation you need – the more you need roller coasters, discos, and excitement just to feel normal. Anyway, Ram Dass talked about all that he learned in those two months, just sitting in that room without leaving; he learned that boredom is just a lack of paying attention. He got to know the cracks on the wall so thoroughly, and made friends with a spider on the window sill, and got to know its habits perfectly.

Also, he brought a couple of bags of Peanut M&Ms with him, and, traditionally in Buddhist monastic practice, one does not eat meals after noon. So, right before noon, at maybe a quarter to noon, he would eat two Peanut M&Ms. He figured out that the amount that he brought worked out so that he could eat two a day, and he would take his time with them. So, he said, it was such a rich experience, it was almost too much, just the salt, the crunch, the chocolate, the sweetness, the peanut, all of it …

He was back in America a couple of months later, talking with someone, and he just shoved a bunch of Peanut M&Ms in his mouth, and later he noticed that he had not even noticed the taste. He there and then noticed just how much paying attention can make such a difference. He realized how much of a rich experience it had been in Burma just because his mind was right there with it, just paying attention to how it felt to eat.

I remember I took a class I have an undergraduate degree in psychology, and I remember learning that more and more researchers think that we are born with personalities, that we are born with definite habits of mind, that there are genetic dispositions or prenatal experiences that we have. I believe that most mothers and fathers will agree that babies are born with personalities. With that said, let’s say for simplicity’s sake that we basically do have a “tabula rasa”, that we are born a blank slate at birth, that we are born broadly open to any and all experience.

In this one human development class that I took, the analogy that was made is, we start with an open mind, like an absolutely flat landscape. But, our habits of thinking and our habits of reacting are like trickles of water on the landscape, where the water keeps flowing in the same pattern. We learn how to pout when our mom does not give us what we want; so, any time, from then on, someone does not give us what we want, we pout. So, that water keeps flowing that way, in those same rivulets. And, by the time we reach adolescence, it is kind of a deep ravine, and it would be pretty hard for the water to flow out of that. By the time we reach adulthood, for some people, their personalities are so deeply set, their ways of thinking are so deeply set, it is like the Grand Canyon. What are the chances that the Colorado River is going to jump out, and go somewhere else, with the walls of the Grand Canyon on either side? Not so likely.

Sometimes, though, when people have a near death experience, or have a great therapy session, or if they read a great work of literature, or sometimes it happens even when someone gets drunk or high, there are things in life that give us what the great psychologist Abraham Maslow called a “peak experience.” All of a sudden we see things differently – all of a sudden, the water jumps out from its river valley, and it flows a different way. “Oh, I can see people in a new way, I can see myself in a new way”, “maybe I could change careers”, “maybe I could love people more”, “maybe I could just go and travel right now”.

The problem is that, then, whether it is neurobiology or whether you just want to say that it is just our habits of mind, when that experience ends, the mind goes back to thinking the same way, the river flows right back into the deep canyon. A lot of times, a brief experience of seeing things in a new way – which we have all had – fades. I think the idea with meditation is to gradually lift up the elevation of some of these river beds, so that the water can flow a new way, so that it does not always flow the exact same way. We do not have to react to people the same way all the time, we do not have to see life the same way all the time, we do not get through like the exact same way we started getting through life when we were twelve or thirteen. Meditation make possible actual change, it says that real new perception is possible, that the water is not stuck flowing the same way that it has always flowed.

Mark Lewis: Oh, excellent, that brings us right to my next question.

Adam Coutts: Great

Mark Lewis: It is really about the nature of practice, and the goal or path to enlightenment. Before we get into that I want to take another quick break. I am Mark Michael Lewis at Money Mission and Meaning. We are speaking with Adam Coutts, meditation teacher. We will be right back.

[Music playing]

Mark Lewis: We are back on “Money Mission and Meaning” with meditation teacher Adam Coutts. Adam you mentioned what you might call a peak experience. I know Ken Wilber – someone who we are both respectful of his work – he sometimes calls it a “peak experience” as in p-e-e-k, like you are peeking into something. When you have that peek/peak experience it can change how you see things, but then you tend to go back into your old ways of thinking.

In this river bed analogy, you are talking about having a meditation practice that lifts the river. I want to focus on that word practice for a little bit because there is something about a spiritual practice which is different than a one-time experience which nothing fundamentally changes. There is something about learning to build a new relationship with your experience. I was hoping you could just talk a little bit about what a practice is, and why they call it a spiritual “practice”.

Adam Coutts: Yeah, that is another great question.

Some people might be familiar with in Buddhism what they call the “eight fold path“, which is sort of the manual for how to practice, how to walk the road of liberation. One of the eight elements of this training is right action, “samyak karmanta” is I think the way it is said in Sanskrit. What right action is – there are all sorts of parts to it – but, basically, the idea is: if you know something is good in your life, and you are doing it, keep doing it. If you know something is the healthy good thing to do and you are not doing it, start doing it. If you know that something is bad for you and you are doing it, stop doing it. If you know something is bad for you, bad for your relationships, bad for your community, bad for your health, and you are not doing it, keep not doing it.

Mark Lewis: That sounds pretty straight-forward.

Adam Coutts: Yeah, it is, but I find inspiration in that. I find looking at it like, “yeah.” What am I doing that is good to keep doing? What could I do differently? Anyway, another part of right action was – do your meditation practice regularly. In the Buddhist context, the idea is: to be regular in one’s practice.

You asked, why is it called “practice”? Well, many times when I teach my meditation class – I have an eight week class that I have taught for a few years now – many times on week two, the second class, people come in and they say something like, “Ah, this is so great! I am doing the same practice as the Dalai Lama, the same practice as the ancient masters. This is so great! I have so much peace and insight this week. I am going to do this forever. I can not believe it has taken me so long to find this practice. This is so wonderful! I just had light energy shooting up my spine, and out of the top of my head.” I then say to them, “I’m sorry.”

Because what inevitably happens to them is in upcoming weeks is that they hit a wall. The metaphor of the spiritual teacher Eknath Easwaran is, you go digging in the garden, and the first two feet is just soft loamy soil, and the digging is so easy, and then you suddenly hit a layer of hard rock, and your hands sting from the shock of the shovel hitting the stone. So, eventually you will run up against everything hard in your life. You will hit your boredom, you will hit your anger, you will hit the parts of yourself you do not fell so good about. You might encounter that conversation last week where you yelled at your friend. You might even encounter some childhood trauma. All of that stuff, any psychological weak point that has not been resolved, will eventually percolate to the surface in meditation. That is when it really becomes a practice. It becomes a practice in embracing those things, making space for them, loving them, being willing to feel them, being willing to sit in the fire and burn for some time in the service of purifying oneself.

Kind of like in a washing machine, the water gets dirty, and that means your clothes are getting cleaner – but, the water is definitely getting dirty. So it is in meditation, that all sorts of difficult, nasty creatures start to crawl out of the sewer. And that is a good sign! It is a sign of progress, but it definitely takes a certain amount of stability, a certain amount of dedication, a certain amount of will to get on the cushion at times when you are in the middle of it.

You know, it is like an athlete that wakes up in the morning, does their crunches, does their sprints, whether they feel like it or not because they know that that training is going to change them into the person they want to be. So it is in meditation, keeping our focus practice, keeping our mindfulness practice, coming back to being aware of, creating space for, and being willing to open to exactly what our experience is, again and again. It often takes quite a sense of discipline and practice.

So … like that.

Mark Lewis: You know, quite frankly it just sounds like a lot of work. I think when people get into it, they realize that it is a lot of work. It is a particular kind of work, though. It is a work that is not necessarily physically difficult. Although, depending on the practice you are doing, you can certainly challenge your mind and body; but there is a particular kind of mental focus that is required of it.

I know for myself it is like working out mental muscles. When you go to the gym, and you have not been to the gym for a while you do some activity, you realize the next day, “Oh my gosh, I did not even know I had muscles that could get sore there.” I often experience, that as I go deeper into my own practice, it is amazing how many different levels (and it seems like there is just an infinite amount of levels), where you realize, “Oh my gosh, I have been loose here. My mind is really loose here”. And, now that I am actually trying to focus it, or now that I am actually trying to be with this experience, I just notice how my mind just runs anywhere else.

Adam Coutts: Absolutely

Mark Lewis: That brings up – you were talking about how the word “enlightenment” is not necessarily the best translation of these experiences. Sometimes I think people approach meditation and enlightenment as, “Okay, you meditate for a while, and then you become enlightened, then you become liberated.” And then you are done. Right? It is over. I mean, game over. You won.

Adam Coutts: Yeah

Mark Lewis: So I ask you a simple question which is – I say that smiling – in your experience what is enlightenment? What is liberation? What is the nature of that, such that people can understand why moving towards that can actually lead to a much deeper and richer experience in life?

Adam Coutts: Yeah, hmmm, you said a lot there. I would love to talk about the nature of practice, the simile of lifting weights, but to deal first with the last thing that you brought out, enlightenment.

One of the first Zen masters to bring enlightenment to America was a guy named Philip Kapleau. He founded the Rochester Zen Center, and he wrote two famous books, named “The Three Pillars of Zen” and “Zen: Merging of East and West.” In those two books, he has a number of kensho stories by his students.

Mark Lewis: What is “kensho”?

Adam Coutts: “Kensho” is a Japanese word that means basically the first stage of “liberation” or “enlightenment”. Basically, what happens is, you focus on your practice – and in his school of Rinzai Zen, a lot of times “practice” means working intensely with these paradoxical stories called koans, or else often meditating on the breath. So, the students do these practices deeply for years while they are sitting on the retreat, while they are at home, even while they go about their daily business. Then, all of a sudden, the mind just pops, and, in these stories of kensho, in these books, the students laugh for hours, or all of a sudden they feel all the weight thrown off their shoulders, and everything becomes totally clear. They feel in harmony with the universe, they feel an open heart with the people around them, life stresses them out less, they feel a sense of energization, they feel a sense of “everything makes sense”, and they feel a sense that – and maybe this is not a very Buddhist way of putting it – of Divinity shining through all things. And then they feel differently forever afterwards, from then onwards.

I believe that such things happen. I believe that there is such a thing that, if a person has a sincere spiritual practice, that there is one moment where the mind just pops. The ancient masters have stories like this. Emerson was walking down a country lane, and all of a sudden he had an epiphany and he just sat there bathed in glory for hours. I do trust that nothing is ever the same after such experiences.

And it is not like a person just sits there like a vegetable. Maybe they still meditate daily, and, generally, they do their thing. I mean, take the example of the Buddha himself. He was liberated, and he lived an extremely dynamic, engaged life after his liberation experience. He might have been the most liberated man that has ever lived, according to certain philosophies and ways of thinking. He practiced after he was liberated, but, none the less, after he was liberated under the Bodhi tree, after his enlightenment experience, nothing was ever the same.

On the other hand there is another school of Zen, Soto Zen, which is the San Francisco Zen Center’s lineage. The teachers in that lineage, they more talk about, “Enlightenment is not a goal. It is not some place you will get to. Just everyday doing your practice, meditating, sitting on your cushion, sweeping floors and chopping vegetables, being with what is, doing what the Hindus call “karma yoga” (an example of which would be to express oneself thoughtfully rather than yell at people when they cut you off in traffic), doing your best to be constructive about the situation and communicate responsibly … all those practices are enlightenment itself. You are not trying to get some where, just in the moment giving your best. That itself is the experience of enlightenment.” Every day, if a person is sincerely walking their spiritual path they will have many moments that feel like, “Ah, this is it, right here, right now, this feels pure.” The teachers in the Soto Zen way say, “That is it. That is enlightenment right there.”

It is not like a bucket of water gets thrown on you, and you are suddenly soaking wet. It is more like walking in the fog. Slowly, little by little, you do not even realize how wet you have gotten, until you are soaked to the bone. You look back on twenty, thirty years of practice and you say to yourself, “Wow, I have become a clear being. I am a different being. I am able to understand people better. I am able to understand myself better. I live in this world, and yet I am not caught in it. There is something kind of I feel the Spiritual Source shining through all things.”

So, those are two different views of liberation and enlightenment, and I think that they both have some validity.

Mark Lewis: Okay. Let’s take that one step further. Which is, in your own practice, and in your own experience, in your own access so what you kind of understand is possible as your mind can both focus and feel the extent of your experience. There is this idea what is the old joke – a Buddhist goes to the hot dog vendor, and says, “Make me one with everything”

Adam Coutts: And then he asks for change, and the hotdog vendor says, “Change must come from within.”

Mark Lewis: [Laughing]

Adam Coutts: Do not get me started on stupid Buddhist jokes, please, or we’ll end up talking about nothing else. Anyway … go on …

Mark Lewis: There is this idea there is this experience of enlightenment, whether it is getting soaked to the bone in one splash, or getting wet slowly through all of the years, there is something about that that seems to point to the same kind of experience that, let’s say, a Christian or a Muslim might experience when they point to being one with God, this God type of experience. I was wondering if you could speak a little bit from as much experiential insight as you can put into words: what is this connection between “enlightenment” or “satori”, and this thing that is sometimes referred to as “God” or “Divinity”?

Adam Coutts: Jeez dude.

Mark Lewis: I know, I am going all the way.

Adam Coutts: You are going all the way. Well, yeah, I think I may be going off the reservation with my answer here. Yeah, this is a great topic. I think that Buddhism often does not use the word “God”. There are various words in Buddhism that I would say translate pretty well to the Western word “God”, though.

There is an amazing teacher who is still teaching, over the age of 100. He is four foot ten, tough as hell, a Japanese named Joshu Sasaki Roshi. He had a temple in rural LA County called Mount Baldy, and he uses the word “God” a lot. It is interesting to study his teachings because his language creates a bridge between, I would say, traditional Buddhist teachings and Western theism.

I would put it this way – and I am not trying to represent Buddhism here, I am just, it is my own opinion, and, as you say, my own experience – I think that Divinity is beyond the human mind’s comprehension – Immanuel Kant, for example, talked a lot about that, how a human being is just not equipped to directly apperceive The Absolute. Let’s say, though, that our Spiritual Source, the Divinity from which all the manifest universe – the trees, the buildings, all the people, the bugs, all the Gorge Foreman grills, all the stars, the whole universe – sprang forth from this Divine Source. And this Divine Source is neither male nor female, it neither exists or does not exist, it is neither good nor bad, it is the totally of the infinite universe that we can see around us, and it is also beyond the universe, or maybe it’s both, or maybe neither. Bottom line, there is nothing that we can really say about it, because are human minds are too feeble to really understand or make direct contact with it. That is what Kant wrote, and I agree with that.

However, there is a way that we can get hints of it. The more we are precisely aware of our subjectivity, the more we have the experience of Divinity can shine forth out of things. There is a way in which this is the essence of Buddhist Vipassana practice. The idea is: if you can notice all of your body sensations, if you can notice all your thoughts exactly as they are, if you can notice all your visual experiences / seeing, if you can notice your hearing – just pick apart all those vibrations and you know, as we said, have the mind accord with the exact shape of those vibrations like a runaway ski caressing a hill. If you can feel the vibrations of all of that, if you can really fell the vibrations of the pains in your knee, the pains in your back while you are sitting there in meditation or even the way your body feels as you are just walking down the street, if you can just notice where your mind goes- how you are distracted by the new pair of shoes in the window, the exact shape of the vibration of that distraction – then you are just noticing the topography of being human. And, then, you begin to see that something subtle and luminous is shining through the cracks between your experience – whereas, formerly, being human was this big solid experience; “I am human. I have this much money in my bank account. I am at war with this ex-friend of mine who does not understand me.” If you can notice this, and see clearly all the aspects of being human, then some light starts to shine through the solidity. And, I think you could say that light is Divinity.

The Buddhists do not use that word. They would maybe call that experience of dissolution of an experience of being a solid, suffering person as “impermanence“, or maybe “no-self”. And, I think that is part of the tricky part. Spiritual practice takes you to the far shore, and it is easier to describe how to get across the water than it is to describe that far shore.

Some Western monotheists and some Hindus describes the experience of the Absolute in the positive, being “full of God”, being full of some experience. And some people describe it in the negative – absolute emptiness, absolute pure consciousness with no contents.

A Christian might experience the Spiritual Source and say, “Hey, I met Jesus”, while a Marxist might say, “Hey, I had a pure vision of the telos of history and the end point of the evolution of all economic systems.” I do not know – people have different words for what it is that they encounter. “I felt the pure Tao”, “I felt the Goddess”, “I met an angel.” Ultimately, I think the words do not really matter. What really matters is people having a personal experience and experiencing it for themselves – the bottom line is have a sincere practice that will take one on that journey.

Mark Lewis: We were talking about how the experience of meditation can usually be likened unto experience of what we call enlightenment, or even how it relates to the idea of God. The idea of practice and path on the way to that, and you didn’t have a chance to answer part of the idea where I had suggested that meditation can be somewhat like lifting weights, where you discover muscles where you didn’t before, and I wanted to give you a chance to get into that, if you could talk a bit about that.

Adam Coutts: [laughs] Thank you, Mark. Yeah, I talked about how there are two aspects to traditional Buddhist meditative practice. One is focusing the mind, intentionally choosing an aspect of reality to focus on and let go of all else. The other one is having the mind accord with exactly what is, being mindful of the nature of what you could call phenomenological experience, or the different sensory experiences that a human being can have. I would say that the whole metaphor of lifting weights is more accurate for the first practice.

If a person is watching the breath and letting go of all distractions, there is a way in which it’s a stupid, repetitive, boring exercise, like playing piano scales, or like lifting weights. The point of lifting weights is not lifting weights. The point is to really have a healthy, strong body. The point of playing piano scales is not to get good at playing piano scales. That might have its limited charms, but the point is to really play beautiful Chopin. The point of watching the breath – similarly, it’s a repetitive exercise, it can be boring, it can seem pointless. For watching the breath, or any other meditation that focuses the mind by letting go of distractions, the point is really to have a mind that is pliable, that is powerful, that is able to intentionally choose what you want to pay attention to.

Plato, the Greek philosopher, talked about how the human mind is like a sailing ship where they’ve locked the captain and the navigator in the hold. The sailors do not know how to steer the ship, they do not know how to navigate, and they can not decide amongst themselves where the ship is going. So it goes one way, towards one island for a few miles, then it goes a few miles towards a different island, then it circles around and goes a few miles towards a still different island. That is often how the human mind is. Samatha focus practice, the practice of intentionally cultivating a sharp composed mind, a mind that is able to focus on one thing intentionally, is the opposite of that unconscious wandering. And, the process of cultivating that often is like lifting weights. It often is steady work.

However, I would say there is an aspect of work to the Vipassana practice also, although less of one. Overall, Vipassana is more like letting reality choose you, rather than you intentionally choosing what you are going to pay attention to. However, I would say with both focus practice and mindfulness practice, there is a way at which there are times in formal meditation practice where it feels like work; where it feels like, “I’m up against my edge. It’s hard. I need to push myself. It’s difficult to push through and really meditate.” Then there are other times, where, from my own experience living as a monk in monasteries, and having a twenty year practice at home, it just feels really grooving, and it is easy, and the practice kind of carries you along. Like in the popular notion of meditation, you are just sort of grooving with the cosmos!

There is a story where the Buddha had a senior student that came to him and said, “I’m kinda confused about this meditation thing”. The Buddha replied, “Well, weren’t you a lute player (which is a stringed instrument like a guitar), weren’t you were a professional musician, before you were a monk?”

And the monk said, “Yes indeed, Sir, I was.”

“And you know how, with a lute string, sometimes you need to tighten the string to have it sound true and on tune, and sometimes you need to loosen the string?”

The monk said, “That is exactly so.”

The Buddha said, “Well, so it is in our meditative practice.”

Sometimes we need to tighten the string. We need to work a little. We need to make a little bit of effort. We need to kind of lift up our spine a little bit more. We need to be a little bit more firm with ourselves. “Hey, I’m not sitting here thinking and vegetating and just wondering what’s for lunch, I actually am meditating, I’m actually going to watch my breath, so I’m going to be a little more rigorous with myself.”

And, other times, we need to put a little more slack into the string. We need to relax a little. We need to let our belly out. We need to just say, “Hey, I’m just trying to notice what is. I’m not trying to regulate the breath. I’m just trying to notice the breath as it is. I can be a little bit more relaxed.”

One more thing, if I may say about this: sometimes in the popular imagination, people think of Buddhism or Zen as, “Hey, it’s all good.” You are heard this phrase, right? Like…

Mark Lewis: “Do not worry, be happy.”

Adam Coutts: Yes, just, “Everything’s OK.” You know, I think sometime in the sixties, or even to this day, people think of Zen as “It’s all Zen”, right? Well, I think that is because if you look at the history of Buddhism, in tenth century China there were monks who were meditating twenty hours a day, and the other one would say, “I meditate *twenty one* hours a day.” They knew all the ancient scriptures by memory, and they were super hardcore monks, and the master would say to them, “Relax. There’s nothing you can do or not do to get enlightened. It’s all good.” That phrase comes from Zen poetry, by the way. “It’s all good.”

Mark Lewis: I didn’t know that!

Adam Coutts: Yes. There’s a Zen poem, Master Bunan, where he says something like, “Die while you are alive, and be thoroughly dead. Then, do whatever you want; it’s all good.”

Mark Lewis: Yes

Adam Coutts: On the other hand, though, that same master would find a bunch of common people sitting around smoking opium and playing mahjong, and he’d scold them, saying, “Get off your lazy butts! You need to meditate. You need to work harder. You need to sweat some blood, folks. Do not just ‘do whatever.’ It’s not ‘all perfect.’ You actually need to stop your opium smoking, stop your gambling, and sincerely engage in a spiritual path.”

So this same master might say to some people, “Hey, relax! Put a little more slack in your string.” And to other people, he might say, “Hey, tighten up your string.” It all depends on what the person needed. So I think there are ways in which meditation is like lifting weights, and other ways in which it’s like relaxing and just grooving with the cosmos. It all depends on a person’s spiritual path. Different directions are appropriate for different people at different times.

Mark Lewis: [laughs] I love the idea of a string being tuned…

Adam Coutts: Yes!

Mark Lewis: … and there’s this balance. You are describing this effort on the one hand, and effortlessness on the other, and it’s not about going towards either extreme. It’s about the balance between them, so that the string is in tune. As I think about that and I experience it, as I imagine a cord that is out of tune, where it’s just not “on”, it’s like there’s this feeling I get of “uuuuhh” and when it comes back into tune, it’s like the vibrations align for my ears, which have my body aligned, and there’s a rightness about it.

Adam Coutts: Yes! And we all know people that are a little “slack”, that we might say, “That might be healthy for that person to tighten up, actually get a job, and quit smoking whatever they’re smoking.” And we all know people who are high-strung. Their string is a little too taut, and we say, “Man, you are going to burst a vein.” We all know times in our own life when we’re a little too tight, and times in our own life we’re a little too slack. So, finding that balance requires paying attention.

Mark Lewis: So that brings up another kind of question, which is: what’s the point of this? I know for myself, when I first started my meditation practice, back when I was in college, I used to meditate, and I was in the bliss state that you were talking about, right?

Adam Coutts: Yes!

Mark Lewis: I’d have these fantastic experiences, and I’d think, “Oh wow, this is really going to change things!” And then, literally, five minutes after I had gotten up from sitting down, it was gone! The whole experience was gone, and I’d come back the next day and I’d sit down, and feel like, “What happened to this experience? I went into this world and I got really clear, and then it disappeared.” Then, through time, I did not even have the bliss! [laughs] So I’m sitting, and I say, “Ok, I’m sitting, and I’m doing this, and I’m doing my focus meditation,” because I was doing focus meditation on a mantra at the time.

Adam Coutts: Yes, yes

Mark Lewis: Then, through time, I went through all these different experiences in my meditation, but what I kept finding was; when I left the meditation mat, most of the experience would disappear. I found for myself that I began taking up a practice where, when I’m get up from the meditation mat, or when I would stop my walking or my practice at the time, I would set aside some time to actually do some writing, or it might be actually when I could communicate with someone, because I’m gotten out of my anger and I was in a really clear space. So I would make plans, or I would do communication. From a real, practical perspective, how does a meditation practice help you in your real life, in your daily life?

Adam Coutts: That is an excellent question, Mark. Yes, an excellent question. That is really interesting. I didn’t know that about you, even though we’ve been friends for a while. Very interesting.

I do think, as you say, when a person is doing formal meditation, when a person sits down and says, “Ok, for this fifteen minutes, or this hour, I’m going to do this formal meditative practice,” it’s not the time to review life. A person might have insights come up for them, they might have creative ideas – but I agree with some of my teachers when they talk about how meditation time is not the time to pursue those thought forms that come up. But afterwards, right afterwards, oftentimes the mind is open, and you are still present to those insights. “It’d be really good to apologize to that person”, or “Here’s an outline of a short story I could write”, or “Here’s a way that I could improve things at work.” I think writing those things down, or just insights that a person has about themselves, “Oh, I’ve noticed that my mind tends to do this” – right after meditation is a really great time to do that.

Mark Lewis: In terms of the benefits of meditation, what real world, practical benefits do they make?

Adam Coutts: I think people generally find that in the short term, sometimes there’s increased agitation. There’s increased hypersensitivity. There’s restlessness. There are all sorts of short term…

Mark Lewis: That is not like fun!

Adam Coutts: Like I said, it’s like digging in the garden. Sometimes you hit a hard level of rock, and yeah, I think, in the short term, people often have difficulty that comes up for them. It’s sort of like if you are on a hill and you want to get to the mountain, you need to walk through the valley. Another analogy I make is: if you have a water system in a house, and in some of the back channels there’s a lot of rust and algae; if you flush the whole water system of the house with a whole lot of high-pressure water, that rust and algae you’ll be flushing you will see coming out of the spigot. You’ll say, “Oh, this is horrible! I’m trying to clean out the water system, and here this rust and algae is coming through.” Well, that is a good sign – it means you have some back channels that formerly you weren’t even aware of what was festering back there, and now they’re getting clean. But when you flush out the whole system, out comes all the old the rust and algae. It only lasts for a while, though, and eventually your whole system is all the cleaner.

So it is with meditation. As you flush out the old back channels, sometimes weird agitated stuff comes through, you might feel more agitated in a given week or month, and the local fluctuations of your mind state are up and down, but, in the long term, the mind gets clearer, it gets calmer. People tend to find that their heart is more opened. They’re more patient. They feel more of a sense of luminous goodness to life. They feel more of a sense of their natural intelligence, and clarity of thinking shines through. There’s less of a tendency towards addictiveness, and more of a tendency towards just being at peace, without addictive rushes. People have more intuitive insight into the nature of things. All sorts of good things can happen.

As one of my teachers says, “If a person is not really clear what the benefit is in a meditation practice, one thing to try is to meditate every day for three months, and then do not meditate for a week, and see how that week goes.” In my own experiments like that, typically that week is agitated. I feel a little panicked. I notice how much the meditation gives me a feeling of spaciousness, patience, the ability to deal with one thing at a time, the ability to give my full attention to people when I’m talking to them.

So, sometimes it’s hard to see the benefits of meditation, and, sometimes, in the short term, things get worse before they get better. But in the long term, having more spacious mind, being in touch more with Spiritual Source, clearing out the impurities in our heart, mind and soul; those can not help but bring all sorts of blessings to a person’s life. The longer one practices, and the more sincerely one practices, the more one finds that these good things are present.

I would say one other thing, which is that: you know, you talked about “daily life”, and I know a lot of what this podcast show is about is the way one makes a living. So, there’s a tradition in Buddhism of meditatoim practice out in daily life. One of the great twentieth century masters that many American Buddhist teachers studied with was a Thai master called Ajahn Chah. If I understand correctly, at Ajahn Chah’s monastery, there wasn’t much formal sitting practiced. A lot of what people did was: they were mindful while cleaning the toilets, while chopping wood, while sweeping the courtyard – I do not know exactly what the nature of the work was.

There’s a way in which we can find mindfulness practice while we work on a computer, while riding the subway on the way to work. I think that there are many opportunities during daily life to clarify the mind. Waiting in the doctor’s office is a great time to check in with, “How does my body feel? What’s the texture of my thoughts?” While riding in a vehicle – as long as you are not the one driving! – is a great time to check in. [laughter] While playing sports, people can bring mindfulness to the practice of running, the positioning of the body. The Buddhist tradition says: practice out in everyday life, while walking down the street, being mindful, being aware of the breath, being aware of the mind, mindful of the impact of sound and light from the outside world.

Meanwhile, the stronger a person practices on the cushion, the more they are able to naturally drop into mindfulness, during a boring meeting at work, or while eating lunch – formal regular practice, or daily practice or weekly practice, can translate to daily life. And being more mindful in daily life really lubricates and facilitates the power and the clarity of regular sitting practice on a meditation cushion. Formal meditative practice first thing in the morning on a cushion helps support our mindfulness in daily life, and vice versa.

Mark Lewis: As you were saying that, you reminded me of something we said earlier. We were talking about really experiencing the texture of pain, or going so deeply into pain that you broke through to the other side into something beautiful. This bringing mindfulness to the activities of our daily life, from one perspective it’s, “Ok, that way I can meditate more.” But from the other perspective, it is really so that I can get the texture and the depth of this experience in daily life, kind of like a blade of grass that, as you really notice it and recognize its beauty, that transports you to this profound understanding of the miraculous nature of life and consciousness. As I was listening, this phrase came into my mind, which was that “meditative awareness or the spiritual relationship with your daily life” is kind of an acquired taste, it sounds like. Something like, the more you taste it, the more you realize how good it tastes, and the more you want that …

Adam Coutts: Yes

Mark Lewis: I want to begin to switch gears into more, shall we say, political topics in a little bit, but we need to take a break first for our sponsors. I’m Mark Michael Lewis. This is “Money, Mission and Meaning” and we’re talking with meditation teacher Adam Coutts, and we’ll be right back.

[music and commercial break]

Mark Lewis: And we’re back, with meditation teacher Adam Coutts. So, Adam, we’re been talking a lot about the internal experience and the lived experience of meditation and the Buddhist practice that you are teaching and that you are worked to cultivate in your own life. I think it’s difficult to talk about religion at the beginning of the twenty first century, and spirituality without it bringing up the context of the political challenges that we’re facing in the Mid-East, and Israel, and Iraq, and even in the United States, the religious attempt to bring creationism back into the schools under the rubric of intelligent design.

I wanted to ask you: how does your understanding of meditation, and your understanding of cultivating conscious awareness fit in with the more national and international political scene, in terms of how people deal with religion in general, and how religion at that level relates to what you are talking about?

Adam Coutts: That is a big subject, Mark, yes! Fascinating question. I think in America, you could say wherever Buddhism has gone, it has morphed; it has grafted itself onto traditional or indigenous religious thought. So, in Tibet, Tibetan Buddhism shows a lot of aspects of the pre-existing shamanic tradition called Bon. You could say Chinese Zen took on much of the language, practices, and world view of Taoism, and Japanese Zen with Shintoism. So too in America, we would find that much of Buddhism has connected with or made an alliance with left-wing politics and with humanistic psychology.

In America, I think Buddhism is often seen as a counter-cultural thing, being aligned with equality or a sort of non-religious religion. I think the fellow Buddhists I have met in monasteries are sort of refugees from religion. They didn’t like Judaism or Catholicism or whatever, they found it too patriarchal or too traditional, and so they turned to Buddhism. They thought that Buddhism could more be what they wanted it to be, and they could more live out their political ideals.

And I think that, in traditional Asia, there are some Buddhists who also see it that way. Buddhadasa Bhikkhu was a great Thai Master in the twentieth century, and he wanted to turn Thailand into a Socialist state, and that was his political orientation.

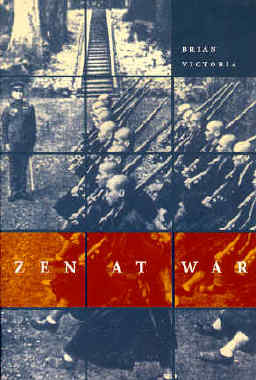

However, I found it eye-opening to read a book called “Zen at War”. It talked about how especially the Zen masters had very much supported the Japanese imperial efforts in the imperial expansionist era, when they conquered Korea and Taiwan and went to war with China and up to Pearl Harbor. These deeply enlightened beings would say these things that are shocking to most modern ears. They were nationalistic, they were pro-war, and they felt the Japanese were superior to Chinese, Philipino, and European people.

I think it’s helpful to realize that Buddhism can mean all sorts of different things, and that there’s no absolute political alignment that Buddhism has. There are some aspects of Buddhism that, to the American ears, would seem left-wing, for example the idea of compassion, the original idea of getting rid of religious rituals. I think the Buddha was also against the caste system. In modern India, many of the Untouchables converted to Buddhism. They thought, “Well, we can’t win with Hinduism, so we’re going to be Buddhists.” But Buddhism is also a religion. In Asia, it stands for the authority of the elders, for chastity, for doing hard self-responsible work. So, there are also aspects of Buddhism that could seem to us as more right-wing. In general, I think it doesn’t really map that easily to the American political spectrum and how we would think of things.

I would say this: there’s a psychologist named Marshall Rosenberg, who has invented a school of personal growth called Nonviolent Communication. I’ve talked with Marshall some, and he told me that he explicitly drew a lot of the principles of Nonviolent Communication from Buddhism. The idea with NVC is that you sit down and dialogue with people, and you really get to the point where you understand people’s feelings and needs. It’s kind of hard to encapsulate in a nutshell, but it’s a way of communicating such that genuine dialogue is fostered, and understanding, openness, and even reconciliation is possible.

Now Marshall Rosenberg travels all over the world, and he works with warring groups in Colombia, Israel/Palestine, the Balkans and all over world. He deals with groups in conflict. I have tremendous respect for what he does, and to my mind, he is a paragon of Buddhism in action, of bringing the essence of the mindfulness experience, of the meditative experience, out into political action and to people in conflict, people’s verbal speech, developing the idea of how a person on a cushion ideally is harmonizing with their own experience in finding a depth there and a richness there and really getting to the heart of the matter. There is a certain liberation or unhooking from suffering that happens there. Marshall has developed a technology of bringing that into interpersonal verbal communication that I have tremendous admiration for. And, so, he is a model for me as to how Buddhism can, at it’s best, play out in the world of politics.

I do just want to underline what I said before. You know Buddhism is a religion and there’s a lot of tradition to it. Sometimes what I see is that the way it is translated in the West is in a counter-culture, groovy kind of way, which is not my take as to how the source religion often is. I think that there are “left-wing” aspects to it, and there are “right-wing” aspects to it. Ultimately, the spiritual experience is beyond both those categories, and transcends and includes them both. If you think about it, the world of politics is the world of conflict is this world of things; ideally, any religious or spiritual path has its aim of putting us in touch with the transcendent or absolute aspect of reality, the aspect where separation, politics, and conflict becomes almost meaningless.

Mark Lewis: One of the ways that I think about meditation is that meditation is the ultimate practice of Buddhist tradition, a more contemplative tradition without the dogma. So, without the beliefs of how the world is, or who’s right and who’s wrong, is it really about, “how do I get in touch with my own experience? How do I learn to be at peace with who and what I am, such that I can then act in the world in a way that is harmonious; that furthers other people’s development and that furthers my own development, in a synergistic way?”

I think the idea of the religion and the meditation can create a whole series of problems. In your classes – you teach an eight-week meditation course that people have gotten a lot of value from. How do you address the difference between the practice and the beliefs of religion? And what do you think about the belief side of it and how it fits into a practice?

Adam Coutts: This is a big question!

Mark Lewis: Yes, I’m asking the tough ones

Adam Coutts: Yes, that is a good question. I’ve had a few students who are uncomfortable with the religious-y aspects of Buddhism. And there are people – Eckhart Tolle is one example of this, and definitely Jon Kabat-Zinn has written some best-selling books – who take the mindfulness of Buddhism, and they present it stripped of the religious context.

When I teach though, in respect to the lineages and respect to my teachers, I definitely teach meditation in an explicitly Buddhist context. And I think most people come to my class being comfortable with that. I would say that any religion is definitely going to have a certain amount of dogma. When I’ve been a monk, there are times when it feels suffocating to me – the heaviness of Buddhism and the tradition – and there were times when I rebelled against it. I have also seen there are ways in which some of the monasteries I’ve been to seem old-fashioned, and they seem unable to fully open their minds. They seem a little attached to Buddhism, as opposed to being a Buddha. But then there are other ways in which sometimes I have rebelled against the traditions, or seen them as archaic, and what was really happening, I realized later, was that I was too immature to actually understand the point of the tradition. There were aspects of Buddhism that seemed stuffy, dead, or oppressive, but that years later I realized were the most beautiful things, and that had been presented to me for my own happiness, and I just couldn’t see it beforehand.

There are many aspects of Buddhism- the Four Noble Truths, the Eightfold Path, the Twelvefold Chain of Dependent Co-Arising – and these “Buddhisty” Buddhist teachings, when I first encountered them, I thought, “That is boring old philosophy. Now, twenty years into my practice, those same teachings seem so powerful and so rich. They seem as real as saying that the sky is blue, or saying that if you want to eat lunch, you have got to go and chop up some food and cook it – that is how you get lunch for yourself (or, you know, go and order it). There are steps to take to get lunch in front of you, and so there are steps to take to be spiritually happy. There are things that have taken me time to really realize the value of.

I want to say, in a good meditative posture we are held upright by gravity. We are held in place through balance, not through muscular effort. We find a balanced posture that we can hold for a certain period of time. A really good meditative posture involves a really upright spine. Let’s say we are sitting cross-legged on the floor: the upright spine holds us up, and then the rest of the flesh of our body just relaxes off that spine. Our arms are relaxed, our belly relaxes, our face relaxes. And I think that is a good metaphor for the balance between religion and spirituality, between having a tradition and the lived spiritual experience.

The traditional aspects of religion, I find, are like that spine. There are certain hard, rigid structures that hold us upright, that discipline us and hold us up against aspects of ourselves that we wouldn’t otherwise want to encounter. And yet, the lived experience of religion, the flesh of the religious life, comes from the Buddha *within*, the Christ *within*, from your moment-by-moment truth. That is like the relaxed belly and like the relaxed face, it’s like the shoulders are relaxed. Whatever is deeply true about life, the universe, and our own internal depths, that is, as the saying goes, our true guru. That is really what is teaching you – really, what is shining forth and informing your spiritual path.

I think in the modern world though, it’s common to say, “I’m spiritual, but not religious.” I have many friends that say this. I think something gets lost in that, though. Ideally, religion is a way of codifying and mass-producing the spiritual experience. Yes, something also gets lost in that too, and yes, commonly it does become dogma. We see that only too well in terrorism, fundamentalism, and all sorts of ways that religion can become destructive. But I also think that we need the tradition, though. We need the lineages, we need practices, we need teachings – that is the upright spine, that is the skeleton that holds the soft flesh of the spiritual experience and creates an uprightness to it, that creates a discipline to it and a non-self-indulgence to it.

I think both aspects are important. Keep coming back to what is real. Keep coming back to what is true. Keep transcending dead dogma. At the same time, be willing to respect the wisdom of the elders. Be willing to respect the past. Be willing to give the benefit of the doubt to things that might seem stuffy or that might seem a little oppressive, and say, “Maybe this is something I do not understand yet. Maybe there is some wisdom here.”

Mark Lewis: That reminds me: Ken Wilber is a big proponent of reviewing the results of your work or reviewing the results of your experiments, whether they’re in consciousness or whether they’re in external science, in what he calls the “community of the adequate.” By “the community of the adequate”, he means people who have already gone through the kinds of experiences you are going through. That way, they can tell. They already know the major mistakes that people are going to make. There’s a truth that goes beyond that “peek” experience again, when you peek into something. When you have an extended set of relationships with it, an extended experience, you get into a deeper understanding with what is true.

It sounds like one of the things that tradition offers, as the way you are describing it, is this deeper wisdom of centuries, often sometimes of millennia, of people working in these arenas and recognizing that there are common pitfalls. The tradition helps you avoid those pitfalls and helps point them out to you. Sometimes, in order to do that, it seems a bit rigid, but that rigidity can be a structure that allows for the freedom.

Adam Coutts: If I may say something controversial – and this is not a Buddhist point of view, this is just Adam Coutts’s point of view …

Mark Lewis: Actually, this is great. I’m going to have you hold that for just a moment. We’re going to take a break. We’re going to come back and hear the controversial thing you are about to say. This is Mark Michael Lewis with “Money, Mission and Meaning”. We’re speaking with Adam Coutts, meditation teacher extraordinaire; again I will say it. We’ll be right back.

[music and commercial break]

Mark Lewis: And we’re back. “Money, Mission and Meaning” with Adam Coutts. Adam, you were just about to say something you said was going to be a bit controversial, not necessarily Buddhist. “This is Adam Coutts speaking.” I am really curious what it is.

Adam Coutts: Great, thank you. I would say that one thing that I find most obnoxious is when modern people assume that we are one hundred percent cleverer than all the people that went before us. I find that I encounter that in writings I read on the web or in magazines, or op-ed pages, or just friends talking about the evolution of society. I think there’s a way in which our natural sciences are definitely showing an evolution. We are understanding the natural world, physics and biology, computer science, better than we did fifty years ago, 100 years ago, 500 years ago. However, I think on a spiritual level, on an interpersonal level, I am not sure that that it is the case.

I think there are signs society is evolving in a really positive direction, and there are also signs that it isn’t. I don’t see it clearly and simply as one way or the other. I think that being willing to say that 50 or 100, 500 or 1,000 years ago might have something valuable to teach us – I think that’s a certain mark of maturity, and something that the modern age could use more of. That’s my opinion alone, that’s definitely not a Buddhist teaching that I am aware of.

Mark Lewis: I think, given the context of what we’re been talking about, that that makes a lot of sense. I know for myself, the famous Mark Twain quote where he said, “When I was fourteen I couldn’t believe how stupid my father was. By the time I was twenty-one it was amazing how much he’s learned in that period of time.” And the other one is, “Go out when you are young and make all of your fortune, before you get old and you realize that you do not know everything.” [laughs]

I know in my own life, another thing that you said that really struck me was that it’s after twenty years that you look back at the tradition, and you recognize the beauty and the wisdom it contains. In the beginning, it was just oppressive and dogmatic, like it’s out of touch and they do not understand. But there’s a deeper wisdom that you can appreciate, because it’s pointing to something that is not obvious. When you are pointing at something not obvious, sometimes people retreat back into poetry. They retreat into less formal, didactic, logical frameworks because you are pointing at something that is subtle, and it’s difficult to get at.

I think it’s true that there’s an idea, if it’s not new, then it can not possibly be valuable. While it’s different from saying, “It’s old, therefore it’s valuable; well that is 4,000 years old, therefore they must have insights that we do not have,” there is a respect that you can offer that is made it through the test of time, to look for what is beautiful. I appreciate that.

I want to shift gears one more time because we’ve talked about religion, we’ve talked about politics … that pretty much leaves sex [laughter]. So, I wanted to ask you about your own experience with yourself and your teachers. There are few things that have a greater taboo in our culture than sexuality, and yet, it is such an essential part of the human experience. Whatever it is that gives us life and gives us consciousness and makes us want and desire, is definitely caught up in the sexual experiences that we have; sexual desires, and the challenges and the possibilities, and the ecstasy of sex and consciousness are somehow deeply related. I’m wondering. In your experience with your students, what is it that meditation makes possible, in terms of being able to actually enjoy sex, or to deal with the taboos around it’s

Adam Coutts: Yes. This is a good question. I would say, in the Buddhist tradition there is a fair amount of disagreement about the role of sexuality on the spiritual path. I think, as I said, much of Buddhism in Asia, as I understand it, not from firsthand experience, but from books and from listening to my teachers talking, it is pretty traditional. Part of the Eightfold Path is, as I said, right action, and part of right action is right sexuality, not harming through sexuality. The way that that is translated is a lot of different ways.

For some traditional teachers, it just means no sexuality outside of procreation within a marriage. You and I live in the modern Bay Area, where there is all sorts of sexual freedom. That sort of point of view by a Christian teacher like Pat Robertson or the Pope is exactly what people rebel against. They say, “That is ridiculous.” But, you’ll find strands like that in Buddhism. I’ve heard it said that the current Dalai Lama has said that homosexuality is inappropriate, which shocks a lot of American admirers of his. I do not know if that is true, but I have heard it said that he said that.

On the other hand, there were other Buddhist teachers like the wandering Zen Master Ikkyu, who lived in medieval Japan. His practice was getting drunk and going to brothels, and spreading the Dharma to the prostitutes. His whole thing was that Dharma is everywhere, that the truth is everywhere, that the moment is everywhere; that compassion is everywhere, and that it should nit just be restrained to the temple, that we do live in the world with all of its messiness, with all of its color. He said, let’s take it to the rough side of the tracks, spreading the Dharma there is as important as spreading it to the proper people. Yes, I would say there are different traditional Buddhist teachings there.

Changing subject slightly, in my own life, meditative practice definitely helps to enjoy sex. It helps to open my heart, it helps to have me be present, to have me be in my lived experience as opposed to my thoughts, which all help create sexual pleasure.

I would say more than anything else, though, you know Buddhism is a religion, and a lot of what Buddhism is about ethical action. I am single, I’m not married, and, in my dating life, I think that it’s important for me to be honest with people. It’s important for me to have an open heart in my dating life. I find that my Buddhist practice is absolutely integrated in dong my best towards being successful in those endeavors. Does that answer your question?